While we reference popular indices for context, our portfolios are constructed independently and are not bound by index composition or short-term performance considerations. This flexibility allows us to think clearly, act deliberately and invest when we think the odds are in our favor.

Our investors include foundations, endowments, municipalities, family offices and accredited investors.

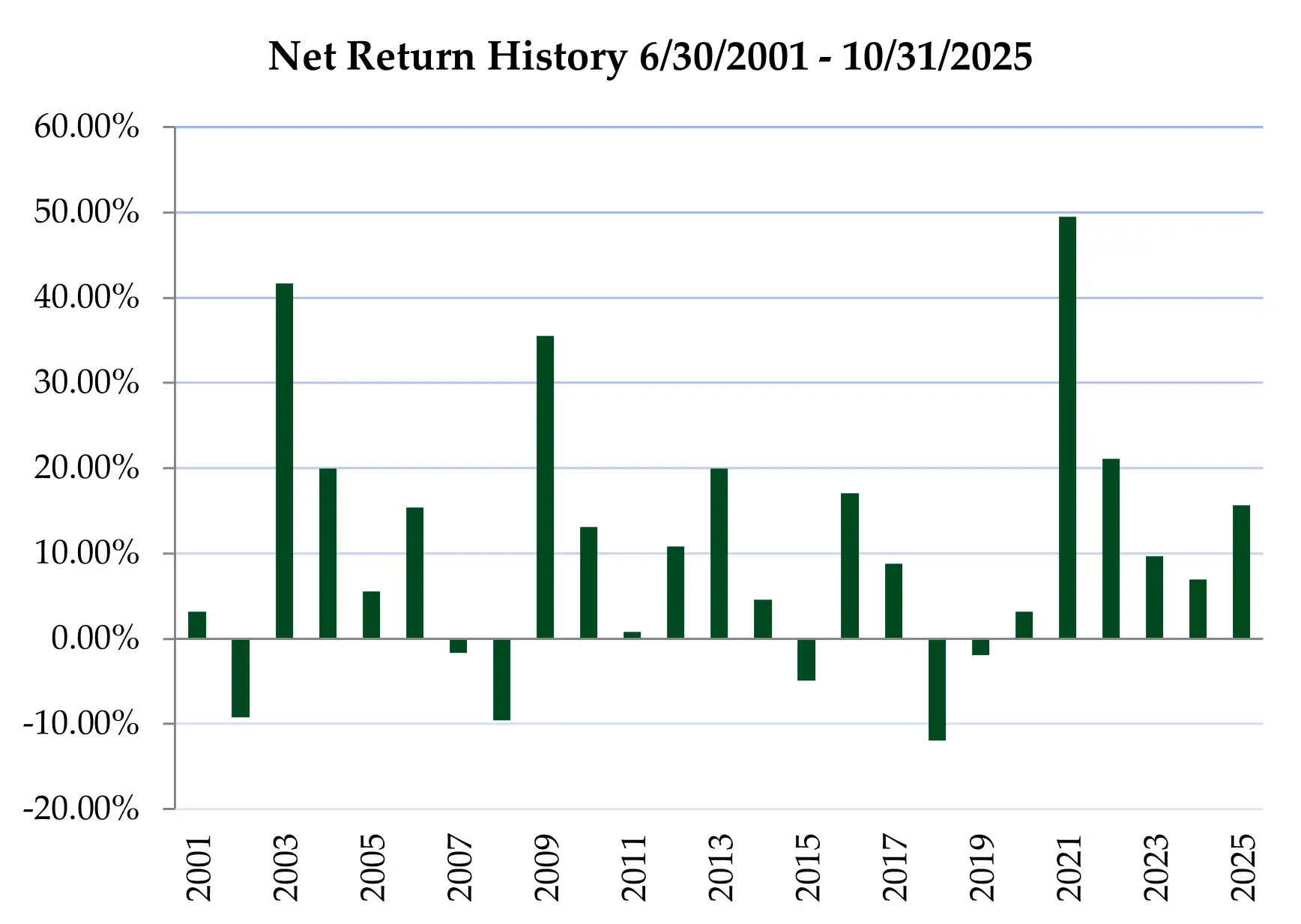

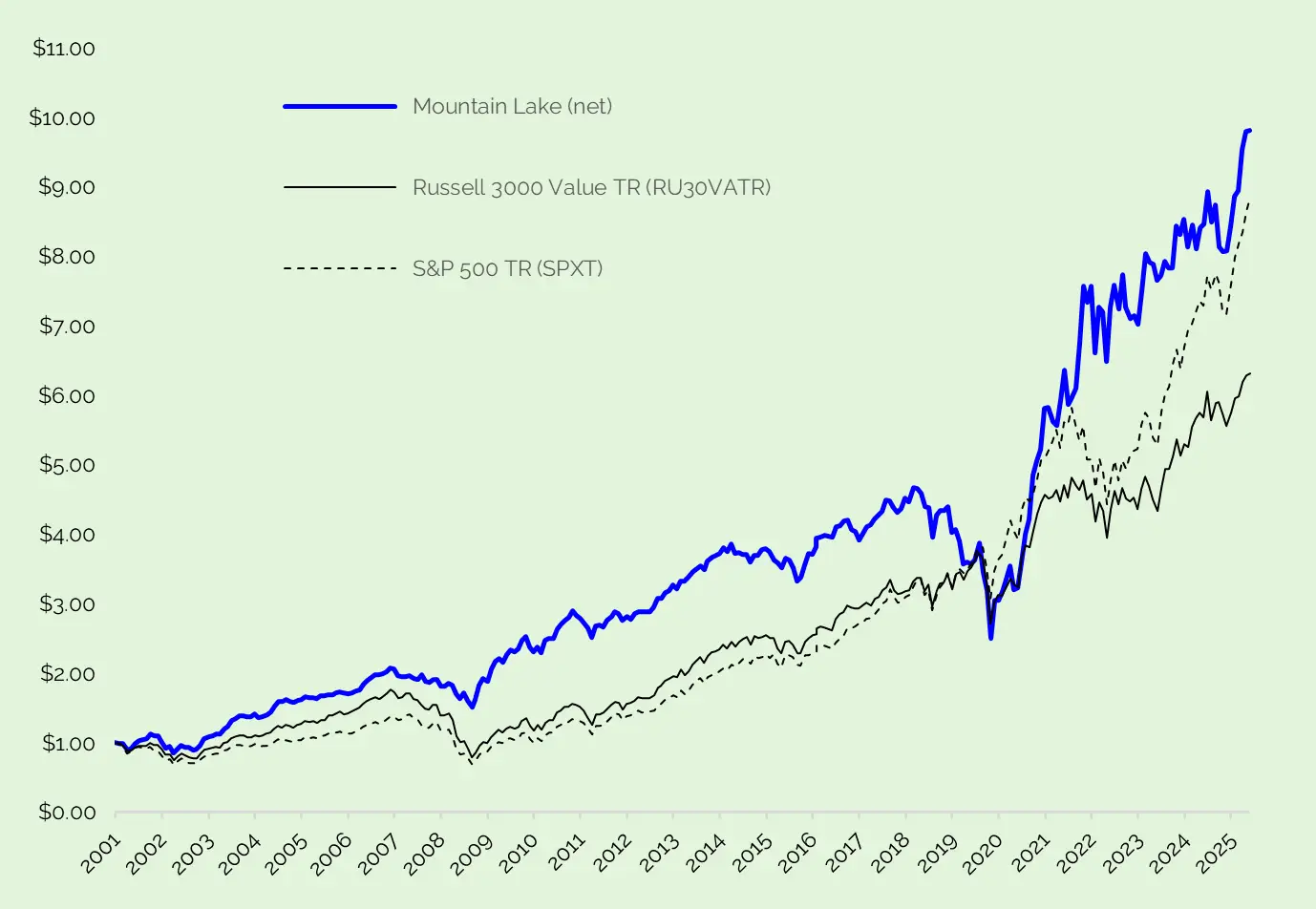

We have cumulatively outperformed the Russell 3000 Value and S&P 500, net of fees, since our inception in 2001.

We pursue an opportunistic strategy focused on generating positive returns throughout market cycles with lower volatility than traditional benchmarks.

Rather than follow indices, we target mispriced opportunities across sectors, industries and market caps, often arising from dislocations creating attractive entry points.

What sets up apart is our broad mandate, original research, management alignment, coupled with our ability to think independently and invest selectively, position us as a leading active manager.

Phil has a long track record of leadership and value creation. Phil was formerly the Chief Executive Officer of Aimia (TSX: AIM) and a member of its Board of Directors from 2018 to 2024. Prior to that role, Phil was the CEO and President of Mittleman Investment Management (MIM), a value-oriented SEC-registered investment adviser, which was acquired by Aimia. As CEO of Aimia, Phil monetized over $1 billion in assets and transitioned it into an investment holding company. Prior to founding MIM, Phil was Managing Partner of three venture capital funds with liquidity events of over $1 billion during his tenure. Phil began his career at the Kushner-Locke Company after attending Kent School and Trinity College. He has also served on the Board of Directors of Providence House, and volunteered for 12 years as a Big Brother in the Big Brother program.

Eugene began his career in 2005 at Citco Fund Services as a fund accountant. Over his six-year tenure at Citco, he held positions as senior accountant, supervisor and manager where he led teams responsible for the administrations of multi-billion dollar private alternative investment funds. In 2011, he became an outsourced controller for emerging fund managers, assisting with their formations and developing their accounting, operations, and compliance processes. In 2012, he joined Mountain Lake as Chief Financial Officer overseeing the firm’s operations, including accounting, legal and compliance. Eugene holds a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration from the University of California, Riverside and an MBA from the University of San Francisco.

We place great importance on investing in companies with management teams that share our philosophy on capital allocation. We attempt to understand management’s motivation and evaluate their logic and actions. We then assess the quality and likelihood of success of the allocation decisions.

"[Owner earnings] represent (a) reported earnings plus (b) depreciation, depletion, amortization, and certain other non-cash charges less (c) the average annual amount of capitalized expenditures for plant and equipment, etc. that the business requires to fully maintain its long-term competitive position and its unit volume. (If the business requires additional working capital to maintain its competitive position and unit volume, the increment also should be included)…"

- Berkshire Hathaway 1986 Shareholder letter

Said another way, owner earnings are the cash which would pile up on the balance sheet before returning any capital to creditors or owners, if the company chose to fully defend, but not expand, its competitive position.

The goal of capital allocation is to maximize the value of future owner earnings per share. The most successful allocators are the ones with a combination of clear logical guidelines and maximum flexibility for capital allocation.

The value of flexibility in allocating capital is under appreciated.

Wall Street bankers and analysts pressure companies to offer easy-to-model frameworks which precisely allocate capital to different buckets. They are in the modeling business so the less guessing they must do, the more accurate their models. Accurate modeling is not the same thing as maximizing returns. Bankers and analysts do not add value to companies which do not need capital markets. They are a management distraction.

Similarly, short-term traders are interested in price movements around earnings releases and other events. The less variable the allocation decisions are, the easier it is to predict results.

Pleasing analysts and short-term investors is not optimal for long-term corporate returns. It is evident that management which run companies for their owners and not the forecasting community prefer the freedom necessary to optimize their returns. If well executed, those companies compound investment value at the highest rate and attract long-term owners. It is useful that management be clear and transparent about its objectives but not its tactics to best serve its long-term owners.

There are five options to allocate capital: 1) invest in the existing business to expand it beyond its current competitive position, 2) make an acquisition, 3) pay off a creditor, 4) return capital to shareholders either via share repurchase or dividends and 5) hold onto the cash.

To optimize the returns from capital allocation, all decisions should be ranked according to the expected internal rate of return (IRR) of each potential option. Ranking the returns by IRR from highest to lowest, is sometimes referred to as stacking returns. Assuming the balance sheet is at its target leverage, ideally management uses all available owner earnings for the highest risk adjusted return opportunity and moves down the list stopping when they have exhausted the owner earnings. If there are limited high return investments available and none expected for the foreseeable future, the capital should be returned to the owners.

This requires judgment not just financial analysis. The value of retiring debt by an over leveraged company is greater than the interest expense avoided as the risk of insolvency is mitigated and future opportunities may require a strong balance sheet. The value of holding onto cash is not only the interest earned but includes the value of investment opportunities which may arise in the future. Nonetheless, the highest returns should generally be pursued and the lowest avoided. It is that simple.

When companies make acquisitions for “strategic” reasons, that usually means they overpay, and the stock price will suffer permanently. This is usually the case for acquisitions to get to “critical mass.” Sometimes there are strategic reasons that appear to make sense. For example, a low return acquisition might seem necessary to avoid the significant deterioration of a company’s competitive position. In that case, the base business’ value was incorrect. This means the company was lacking the capital required to stay in place competitively and owner earnings were overestimated.

Acquisitions which are expected to boost the company’s competitive position should be accompanied by a suitably high return. Since IRR is a perpetuity calculation, it is never justifiable to knowingly invest at an inferior rate of return. The best companies audit all their acquisition activity for years post-acquisition to learn whether their estimated returns were exceeded or missed and to learn from any mistakes. Some companies attempt to audit the returns on acquisitions they did not make.

The decision about whether to return capital to shareholders varies depending on the opportunity set the company is facing. Rational shareholders want the undeployed owner earnings distributed if they think they can do a better job with the capital than the company can. As a rule of thumb, if a company cannot achieve at least a risk adjusted 10% unlevered return on its owner earnings, they should return the capital. Conversely, rational shareholders do not want a distribution if the company can do better than they can.

Many management teams (and politicians) harbor the incorrect notion that share repurchase is a “one-time benefit” or even destructive of value. They think that only capital deployed in a business offers enduring value. This is not true. This can be modeled to see the compounding effect of share repurchase today on future owner earnings per share in a growing business. The shares retired today gives a gift into perpetuity as the owners have a larger share of the business forever. A rational long-term owner is only concerned with the growth of value on a per share basis.

If the shares are inexpensive (the IRR expected on repurchase is high) the returns to shareholders are often superior to what the shareholders are likely to do with the funds. It is more tax efficient to buy back the stock than pay a dividend and have the investor buy more shares. In many cases, share repurchases produce a superior risk adjusted return to that which the management can earn with the funds through other investments.

However, management incentives are not typically aligned with owners which creates a conflict when decisions are made. Management compensation is often tied to the size of the company and not the owners’ returns. The expenditure of owner earnings is not at the sole discretion of company management. It is deployed consistent with the views of the owners’ representatives who are the Board of Directors. Board composition matters. The best boards have members who own personally significant amounts of stock which they have purchased with their own funds.

Dividends are rarely desired by rational owners of businesses which have high returns on incremental capital. When dividends are preferred, it is often because the investors don’t trust the boards and managers to hold or invest their money. Owners will also want dividends if the opportunity set facing a business is inferior to their own. There are a few unusual reasons to pay dividends, for example when businesses face unpredictable sudden existential risk (e.g., tobacco lawsuits.) Then, continual share repurchase may not be optimal for long-term shareholders if the entire company may be suddenly overtaken by lawsuits.

At company-hosted investor presentations or conference calls, management can demonstrate what it did with its free cash flow previously and what its policies are. If the company’s goal is that it will deploy capital consistent with that which produces the highest long-term returns, that is sufficient information for owners. If the balance sheet has a target leverage amount or ratio, it is useful to indicate the target and that other uses of free cash flow will be constrained until that target is hit. Specificity beyond that or sharing where the management thinks the best opportunities are, limits the degrees of freedom of the company to pursue what it may view as the best future opportunities.

Nothing says you are on the same page as long-term owners as one CEO who said to us. “When I became CEO, I bought $8 million worth of stock with my own money from my prior career.” We know he cares about the returns on every dollar of owner earnings generated.

There are other related topics such as corporate structures which require dividends, fixed versus variable dividends, dividends versus share repurchase, taxes on share repurchase, hostile bids for the company, share repurchase with large holders, share repurchase with illiquid stocks, and many more. But for now, here are three types of mistakes CEOs and Boards make:

1) Calling attention to the dividend yield – it reeks of promotion rather than information. If it is attractive, it means either the payout is too high or the stock price is too low.

The payout is too high if management is straining its resources, or it can invest in the business, improve the balance sheet or purchase their own shares at a return greater than their owners as discussed earlier. The high payout is a transparent attempt to drive the stock price up in the short term. If the stock price is too low, long-term shareholders will be better off with the return available from repurchase than a dividend.

If there is a reason to return cash to shareholders through a regular dividend, yield should not be trumpeted. It is better to discuss the payout and reinvestment opportunities of the business. The reinvestment rate should provide sufficient funds to allow the company to grow without needing external financing.

2) Buying back stock to offset dilution from stock options – buying back stock is either a good idea or it is not. Making an investment for reasons other than the returns is thoughtless.

As previously stated, the primary financial goal of a management team is to maximize the future value of the owner earnings per share. However, the company must consider that their owners have alternative options for investment capital. Companies which face only low return options on their investments (and high stock prices) serve their shareholders best by returning the capital through dividends. If management makes an investment or buys stock back when the likely IRR on the investment or repurchase is 5% per year for example, while the owners can earn more, the cash should instead be returned to shareholders through a dividend. On the other hand, if the situation is reversed and the corporate opportunity set is large with high returns, no capital at all should be returned. Share repurchase should only be undertaken if there are owner earnings available after investing in every higher return opportunity and it’s still a good deal.

A company may be fortunate to have high returns while selling for a low multiple of their owner earnings. The most successful common stocks over many decades occur when those types of companies, through a disciplined capital allocation framework, consistently repurchase large amounts of their stock. NVR and AutoZone, like Teledyne before them, are legendary to their owners and in the investment community.

The best capital allocation is simply investing in your best return opportunities first and working your way down until you get to your shareholders’ minimum required return or until the money runs out, whichever comes first. Prioritizing something other than returns misses the opportunity to be successful on behalf of your long-term owners.

**The information on this page contains opinions, which should not be interpreted as factual statements. This material is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. There is no guarantee that the views and opinions expressed in this material will come to pass. Investing involves the risk of loss and may not be suitable for all investors.

**The information on this page contains opinions, which should not be interpreted as factual statements. This material is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. There is no guarantee that the views and opinions expressed in this material will come to pass. Investing involves the risk of loss and may not be suitable for all investors.